This article, the first of a series on what it costs an employee to work outside the home, looks at a perennial issue for working parents: caring for their children while they are on the job. The subject is not new—finding reliable daycare has long been difficult and expensive for American families.

The problem varies as the children age: from the need for all-day care for infants and toddlers to after-school care for elementary school children to the sporadic requirement to rescue a feverish seven-year-old or a teen with a broken arm from school premises. Working around school holidays, child sick days, and absentee babysitters is a constant challenge. (The number of children exacerbates the problem.) Each affects a working parent–and the inability to accommodate absences affects businesses.

While the options are varied, they may prove inviable for single-parent or lower-income families:

- Live-in nannies are prohibitive to many.

- The number of licensed daycare providers who take several children into their homes is decreasing.

- Reliable babysitters who come to employees’ homes while parents are at work are reportedly difficult to find.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that the number of licensed family childcare homes and other home-based childcare providers on state administrative lists has declined by 25 percent across the country over the past decade despite the significant demand.1 Similarly, the number of small childcare centers—those serving fewer than 25 children—declined by nearly 30 percent before the pandemic. 2 This does not even begin to address the problem of daycare for a child who is ill and cannot attend school or daycare.

While some parents are fortunate to have family members close enough to care for babies and preschoolers, most do not. Daycare centers, always with lengthy waiting lists, are not just challenging to get into but vary significantly in the child’s quality of care.

Location matters: some parts of the country are far more expensive than others—such as Alaska, Washington, California, the District of Columbia, and Massachusetts. (Massachusetts’s average annual childcare costs amount to $20,880 per child.) The least expensive infant daycare centers are in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, West Virginia, and Alabama.3

Finding Adequate Care is Harder than Ever

Over the past decade, the cost of daycare has risen roughly 36%, outpacing the rise in inflation during that time, according to data[5] from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.4 During the pandemic, $24 billion was allocated to help childcare programs continue in operation, covering areas such as wages and program materials. However, that assistance ended in September of 2023, seriously decreasing the number of childcare jobs and, therefore, the spots available for the children of parents who relied on their service. According to The Century Foundation, more than three million children are projected to lose access to childcare nationwide, and 70,000 childcare programs will likely close.5

Because of the fallout from the lack of this government funding, the majority of responding parents in a recent survey report face an increase of more than $7,000 in additional care costs for 2024, according to Care’s 2024 Cost of Care Report.6

Finding childcare for infants and toddlers under three can be an even more significant issue for employees. The majority of nursery schools and daycare centers admit only children three and who are generally fully toilet trained. Those with a “care-for-twos” program are rare, with limited spaces for these youngsters and often more costly.

Parents are Draining their Savings to Pay for Childcare

Parents of infants and toddlers lose $78 billion annually in foregone earnings and job search expenses because of insufficient childcare.7 This affects both their spending power and quality of life. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) states that child care is considered affordable when it costs families at most 7% of their household income. Yet, on average, according to the Care survey, respondents are spending 24% of their household income on child care (vs. 27% in the prior year), with 60% paying 20% or more (as compared to 67% last year) and 84% spending 10% or more (compared to 89% last year).8

Black median-income households will spend a quarter (25%) of their annual pay ($46,774) on childcare for one child. For very low-income Black households, childcare costs for one child can eat up nearly half (49%) of their annual pay. Conversely, average white American households ($75,412) will devote 15%, and average Asian American households ($100,572) will devote only 11% of their annual pay to childcare. (Wisconsin emerges as the state with the largest daycare cost burden for Black Americans. Black median-income households in Wisconsin allocate over a third (35%) of their annual earnings to cover childcare costs for one child.)9

Working families are making significant sacrifices to afford quality care. According to the Care study, more than one-third (35%) of responding parents report tapping into savings, on average spending up to nearly half of their savings (42%) on childcare and 25% using more than two-thirds of their savings. When asked how long their savings could hold out, a staggering 68% of respondents said they have only six months or less until their savings are depleted. In addition, many report rather radical life changes to support working life with children:

- Working multiple jobs (28%).

- Reducing hours at work (27%).

- Moving closer to family (25%).

- Going into debt (19%).

- Leaving the workforce (17%).10

At Issue: The Impact on Business

The potential loss of employees because one parent has to stay home plus the cost of missed work as a parent cares for a child who is ill is significant: The Century Foundation reports that the loss in tax and business revenue will likely cost states $10.6 billion in economic activity per year if one parent drops out of the workplace. In addition, that group projects that the overall cost to families may create $9 billion a year in lost earnings if a parent has to leave the workforce or reduce the hours worked.11 This situation could clearly have a long-term impact on gender equality at work.

According to a 2023 report by ReadyNation, a coalition of business leaders, insufficient care for children under three depletes the country of $122 billion each year in lost earnings, productivity, and revenue. The analysis found more than double the $57 billion in losses in 2018. Businesses lose revenue due to working parents’ absence caused by childcare issues.12

What Role Can HR and Businesses Play?

Parents look for their employers’ support, while employers often think that childcare benefits are too expensive to consider. However, a number of helpful options vary in cost, ease of implementation[3], and benefit to the employee.

- At the very least, provide employees with a childcare directory of vetted local services: daycare centers, licensed in-home caregivers, after-school options, etc.

- Make work schedules predictable. An unpredictable work schedule[4] can make it hard for working parents to schedule their childcare needs, as rearranging babysitting at a moment’s notice is almost impossible.

- Work-from-home options and flexible scheduling are often the easiest and least expensive to implement. Flexible scheduling allows a parent to meet a school bus or drive a child from school to an after-school program when necessary. Note that flexible scheduling is deemed the number one perk that employees seek.

- Educate employees about their tax options. The Child and Dependent Care Credit is a tax break specifically for employees to help offset the costs associated with caring for a child or dependent with disabilities. (See the Employer Guide to Childcare Assistance and Tax Credits | U.S. Chamber of Commerce (uschamber.com).)

- Employers can offer childcare subsidies in two ways: direct payments to employees with children or partially subsidizing childcare with select care centers or certain childcare workers, thus sharing the cost of childcare with their employees.

- Flexible childcare spending accounts provide employees with choices and are highly effective and moderately inexpensive. Dependent care flexible spending accounts (DCFSAs) can fund the care of children under 13 years old. Parents can withhold money from their paychecks before it is taxed to pay for preschools, nannies, and transportation costs. Employers can provide matching funds. This way, businesses can contribute to employees’ childcare without dictating how they spend their money.

- Consider contracting with a backup[6] assistance program to offer complimentary emergency childcare at an employee’s home or at the provider’s local location to cover child sick days, school snow days, or other one-time emergencies. Companies can structure backup childcare assistance benefits as they do sick days: Employees are entitled to a certain number of days, after which they may pay a partial fee per day for the services.

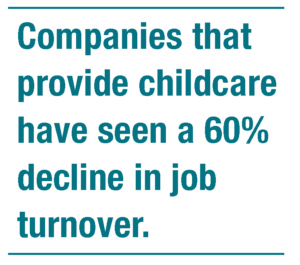

- The more expensive option, onsite daycare facilities, are rare but highly valued by working parents where they prove a high retention medium. Currently, only 17 Fortune 100 companies offer some form of onsite child facilities, mainly at headquarters and not all locations, depriving workers who may need most of the service. However, 24% of the Best 100 Places to Work provide onsite daycare, which undoubtedly contributes to their ranking.13

Working parents make up the bulk of the workforce. Helping families navigate the best choices for caring for their children during the workday boosts retention, worker morale, gender equality, and a healthier balance between work and family life.

Endnotes

1 “Home-based Early Care and Education Providers in 2012 and 2019: Counts and Characteristics,” National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, May 2021, https://bit.ly/3IItPAX.

2 Child Care Cliff: 3.2 Million Children Likely to Lose Spots with End of Federal Funds. Julie Kashen, Laura Valle-Gutierrez, Lea Woods , and Jessica Milli. The Century Foundation. June 21, 2023

3 How Much Does Child Care Cost? 2024 Cost of Care Survey. Care.com Editorial Staff. January 17, 2024, https://bit.ly/3VpzWlo.

5 Child Care Cliff: 3.2 Million Children Likely to Lose Spots with End of Federal Funds. Op. Cit.

Child Care Cliff: 3.2 Million Children Likely to Lose Spots with End of Federal Funds

6 How Much Does Child Care Cost? 2024 Cost of Care Survey Op.Cit., https://bit.ly/3VpzWlo.

7 $122 Billion: The Growing, Annual Cost of the Infant-Toddler Child Care Crisis. ReadyNation. February 2023, https://bit.ly/4924CMs.

8 Federal Register; Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Program, https://bit.ly/43nV3pY.

9 The Childcare Cost Burden for Low-Income Households Around the U.S. – United Way NCA. United Way NCA (National Capital Area). October 14, 2023, https://bit.ly/4cfy6cR.

10 How Much Does Child Care Cost? 2024 Cost of Care Survey Op.Cit., https://bit.ly/3VpzWlo.

11Child Care Cliff: 3.2 Million Children Likely to Lose Spots with End of Federal Funds.

12 $122 Billion: The Growing, Annual Cost of the Infant-Toddler Child Care Crisis. ReadyNation. February 2023, https://bit.ly/4924CMs.

13 Onsite Child Care | Learning Care Group, https://bit.ly/3Tk5IgZ.

Human capital management (HCM) is the comprehensive set of practices for recruiting, managing, developing and optimizing the human resources of an organization.

A structured approach to changing the mindset and perceptions of individuals, groups and organizations to accept and implement new ideas and processes in an organization.

The structured process of integrating an application into workforce processes. It includes the installation, configuration and data population and testing of an information technology system. Putting in place a collection of components and objects to perform that function they were designed to do.