Organizations that are effective at identifying, developing, and placing their best talent in key leadership roles will be the ones that continue to drive sustainable growth over time. A rigorous approach to differentiating people with future leadership potential is the only way to ensure effective succession planning. Successful differentiation is one of the reasons why so many organizations are increasingly turning to the use of formal assessments for development and decision-making (see the recent Workforce Solutions Review article by Church, Scrivani, and Graf and the SHRM Foundation report “Selecting Leadership Talent for the 21st Century Workplace” under suggested readings).

One of the most popular tools in the talent management toolkit is the 9-box model. Although the origins of the 9-box date back to the 1970s with the work McKinsey was doing for GE, it became increasingly prevalent in the 1990s when research on leadership potential emerged from CCL and thought leaders such as Bob Eichinger. Today, benchmarks have reported that over 95% of well-known organizations conduct formal talent reviews. The 9-box approach is one of the most commonly used tools in this process (see the TM benchmark studies under suggested readings). Despite its popularity, companies struggle to use the 9-box effectively; many have found it doesn’t deliver on the promise. Why is this? Because they are doing it wrong.

Why the Traditional 9-Box Model is Broken

The intent of the 9-Box model is based on a simple 2×2 matrix construct that has been popular for decades. You put performance on one axis and potential on the other. Theoretically, the resulting grid of 9-Boxes (using a 3×3 scheme as many companies do) enables line leaders and HR professionals to segment talent based on high performance and potential. Unfortunately, we have heard from many colleagues over the years that the discussion quickly devolves into which box the person belongs in versus a discussion of the underlying talent and their development needs.

This phenomenon, known as “the performance-potential paradox” (see the Strategy-Driven Talent Management book chapter by Church & Waclawski under suggested readings), happens for two reasons: (1) both the performance and potential measures being used in most 9-Box approaches are fundamentally flawed and biased, and (2) the presence of a grid gives leaders a perceived sense of scientific rigor when in fact there is no science behind what they are doing. All of this results in the wrong discussions using the wrong criteria. Worst of all, despite what many think, the 9-box by itself is not an approach to identifying potential since potential itself is one of the categories!

Five Key Steps to Having a Best-in-Class 9-Box

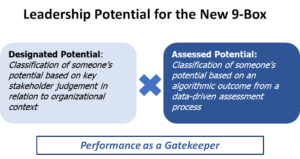

In our collective experience as HR executives at PepsiCo for over 40 years and another 30 combined as external consultants, we have found a better approach to the 9-Box. One that helps clarify the discussion uncovers and challenges inherent biases in how executives think about their talent, significantly improving bench planning and success over time. To do this well, however, requires new thinking about the difference between what we call “designated” vs. “assessed” potential and unboxing the 9-box to change the focus of the talent discussion.

- Throw Out Performance Ratings – They Should Be a Gatekeeper, not a Predictor.

When we say throw out your performance ratings, we don’t mean from your performance management process. Just don’t use them for your 9-box framework. Performance should be used as a gatekeeper for talent discussions, not as a proxy or indicator of future potential. Why? There are three essential reasons. First, despite what many managers think, decades of research have shown that current performance only predicts future performance in the same role or roles of similar complexity. They might be great for discussing success in lateral moves, but they will not effectively tell you who will be the next EVP or CEO. Performance offers face validity by adding quantitative data in a nicely formatted grid, but this is merely pseudo-science. The whole point of focusing on potential in talent reviews is determining who will do better in more prominent roles, not the same ones.

The second reason not to use performance ratings in your 9-box is that performance ratings aren’t objective measures. While management by objectives processes measure outcomes such as revenue, market share, profitability, etc., often the final ratings are influenced by intangible factors outside the influence of the individual. For example, compensation outcomes can play a major role during performance calibration, whether due to forced distributions, stock grants, merit budgets, and bonus targets. Moreover, many managers consider retention, engagement, and potential in determining what rating to give their employees. The latter is double counting, which is what we mean by the performance-potential paradox. How can one expect a 9-box with performance ratings to be objective in this context?

Finally, performance is not normally distributed, making the difference between a 3 or 4 on a commonly used 5-point scale almost meaningless to interpret beyond a certain point. Using performance as a gatekeeper to the entire process is far better. Simply put, you should only include people for talent discussions (in the 9-box) if their performance is average or better.

- Keep Your Current Talent Framework and Embrace it – But Relabel it as Designated Potential.

The concept of potential has been used in organizations for decades. For years, Managers have classified talent based on different inherent models, frameworks, experiences, values, feelings of similarity, seniority, and other inputs. Consequently, getting a group of managers and HR professionals to agree on a single definition can be difficult. This debate stems from the fact that potential is not one single thing for a given individual. Instead, it can be thought of in several different ways, including general potential (what everybody has), leadership potential, and destination potential (see the article in Training Industry.com by Church under suggested readings). However, the one element most “common definitions” of potential have is that they are based on perceptions. These perceptions ultimately result in a classification or label during annual talent cycles. In other words, most high-potential talent calls are subjective designations of potential by a manager assigned once a year. Thus, when used in a 9-box context, judgment plays a vital role in discussing how talent is perceived and what actions should be taken to develop people further.

Does this mean the internal talent calls and designations should be eliminated or replaced entirely with data? Perhaps surprisingly, our answer is no. As the saying goes, “perceptions are reality,” and the judgments made influence the future promotions and success of the leaders being discussed. So instead of constantly reengineering and redefining potential to “get it right,” organizations should embrace their internal model, apply it consistently and with as much definitional clarity as possible, and relabel it for what it is. Unless psychometric behavioral data is involved, it’s not an “assessment” of potential. Its designated potential is defined as the “Classification of someone’s potential based on key stakeholder judgment about organizational context.” While many traditional 9-box approaches today use designated potential as their basis, they don’t always recognize it for what it is. Designated potential is essential in the new 9-box but only when compared with the next component – assessment data based on the science of leadership potential.

- Introduce the Science of Leadership Potential – By Using Formal Assessments & Data.

While internal perceptions and judgments of potential are important, using designated potential alone only gets you so far. If that’s all you have, you don’t need a 9-box. It would be more effective and insightful if you introduced the science of potential using formal psychometric assessments of leadership capability. We call this assessed potential, i.e., the “Classification of someone’s potential based on an algorithmic outcome from an assessment process, distinct from designated potential.”

We know from decades of research that potential is best predicted by a combination of foundational factors (personality and cognitive skills), growth factors (learning agility and motivation), and career factors (leadership competencies and functional knowledge). By using a best-in-class approach to assessing these components, framed in the leadership language of your organization, you will have a robust, relevant, and objective set of insights on your talent (see the recent article in Workforce Solutions Review by Church, Srivani, and Graf under suggested readings for more).

Benchmarks of top companies over the past decade tell us that most companies use some form of assessment (86%) and have formal high-potential programs (79%). Yet far fewer (only 36%) use their data to identify or confirm potential. This represents a genuine opportunity to capitalize on delivering better, more effective talent management and succession processes (see the Workforce Solutions Review article by Ulrich, Church, Eichinger, and Pearman under suggested readings). Other forms of objective data can increase the quality of your 9-box, such as 360 feedback or future-focused simulations, as long as the data measures facets of leadership capabilities that predict potential and not outcomes (i.e., no survey or performance data).

In sum, the new 9-box uses internal judgments in conjunction with objective data and raises the quality of the discussion to an entirely new level.

- Don’t Box Yourself In – Determine the Right Size Grid for Your Organization.

Debating boxes is one of the most significant issues with using the “traditional” 9-box approach for talent planning. In talent review meetings, there is often an inordinate amount of time and effort spent arguing about what box to place people in versus discussing what to do with the talent itself. As a result, time runs out before a substantive discussion about bench implications and talent development actions can be held. This misuse of meeting time is unfortunate and another reason why the 9-box is often seen as ineffective.

When it comes to the new 9-box, avoid getting stuck on the number of boxes. Organizations’ tendency to dogmatically attempt to apply all nine boxes instead of using a more simplified model of, say, 4, 6, or 8 is a mistake. Unless you have a very nuanced set of designated potential categories supported by a robust data set, this will not work.

There is nothing magical about the number of boxes in the 9-box model. It can even be as small as a 2×2. What is essential is that the approach you take makes sense for your organization and can be used to make good decisions. The choice of boxes to include depends on how many you need and what your talent data can support. This decision means the number of designated potential categories you use in your talent management system (e.g., high potential, promotable, develop in place, concern) and the validity and completeness of data you’ll use for assessed potential. What you select should be based on what gives you a meaningful way of comparing designated vs. assessed potential for your talent reviews and planning purposes.

Often, companies don’t need as many designated potential categories as they have, and these should be streamlined to the smallest usable number. We have seen organizations try to use categories that are far too nuanced to be practical. For an effective 9-box, less is more. Fewer boxes mean less time spent arguing over the placement of people in boxes, more confidence in the categorization of talent because your categories are fewer and more straightforward, and more time spent discussing development and actions. This approach puts the time and effort where it should be and yields better results.

- Use Data to Diagnose the Gaps – Between Designated Potential and Assessed Potential.

Finally, despite what many would like to believe, there is no one “truth” regarding potential. Consequently, the 9-box should be about something other than debating potential or finding the correct answer. It should be about understanding the consistency between what the organization thinks of its talent (designated potential) and what the data indicates against a validated predictive model (assessed potential). In this context, the focus turns to each of the boxes in your grid in a diagnostic discussion, not a labeling exercise.

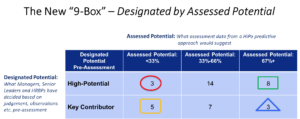

The figure below presents sample data using a 2×3 matrix (6-box). On the left is a simple approach to designated potential (high-potential and key contributor), and on the right is assessed potential broken up into thirds. Note that no labels are used for any box. Assigning labels is not the point. The point is to focus on why different individuals are in each box and what actions should be taken.

Let’s take an example (see example). The eight leaders in the upper right are those whom the organization feels strongly about their future capability, and they did exceptionally well on the data. These people are the ones to continue developing for succession. Similarly, those 5 in the lower left are key contributors with lower assessed potential. They are doing just fine in their current role. Just be sure they are paid well, recognized for their contributions, and are fully engaged.

The individuals in the upper left and bottom right are significant. The organization “loves” the three on the upper left, but the data shows they may have critical outages. The question is, why? Going deep into the assessment results for each of these individuals will help diagnose where the outages are occurring. They might be coming from poor 360 feedback results, key personality derailers, a lack of strategic thinking capability, or poor performance on a simulation designed to test decision-making in novel situations. All of these have different implications for developmental support.

Similarly, on the far right are 3 individuals who are seen as having no or limited designated potential and yet scored in the top 1/3 of the assessment results, indicating a significant disconnect. The first question is, are there any inherent biases (e.g., diversity, gender) impacting the judgment of their potential? Going deep into their results and reviewing their strengths can be helpful in challenging misperceptions. Ultimately, organizational culture fit, prior experiences, or other intangibles (e.g., the right set of skills) might be legitimate reasons for their designated potential category. However, if there are biases there, they need to be addressed. We believe that managers own their designated talent calls (not HR or TM) and should be held accountable for the outcomes after making decisions.

In closing, the 9-box is not about identifying potential; it is a tool for making good talent decisions. If it is to be effective, it must meet two criteria: (1) it enables leaders to classify talent based on designated vs. assessed potential, and (2) it generates a meaningful discussion about the right set of developmental and organizational actions for the talent under discussion. If the 9-box does not meet both objectives, what was designed as a relatively simple framework for discussing talent becomes a source of conflict and consternation.

Suggested Readings

- Unleashing The Power of Assessments for Leaders and their Organizations – IHRIMedia (ihrimedia.com)

- Selecting Leadership Talent for the 21st-Century Workplace (shrm.org)

- How are top companies assessing their high-potentials and senior executives? A talent management benchmark study. (apa.org)

- How are top companies designing and managing their high-potential programs? A follow-up talent management benchmark study. (apa.org)

- Take the Pepsi challenge: talent development at PepsiCo – EconBiz

- How To Identify and Assess Leadership Potential on Your Team (trainingindustry.com)

- Why Talent Management and Succession Bench Building Aren’t Working Today: At Least Not as Well as They Could! – International Association for Human Resources Information Management (ihrim.org)